Joseph Eichler built the Bay Area in his own image.

Even those of us who have never lived in an Eichler home inherited the design and development sensibilities that he promoted with the thousands of residential units that he scattered across the region like dandelions; when it came to the post-war housing boom, Eichler was not just the man with the plan, he also drafted that plan.

But there is also a certain degree of tragedy in the Eichler legacy. While some municipalities make bids to preserve Eichler homes, city and state governments struggle to rescue the greatest Eichler development of all: access to livable, secure housing for everyday people.

I Like Eich

One of the first pieces of advice I ever got for writing about housing in the Bay Area is that local readers love to check out Eichlers on the market.

This seemed like good, practical know-how, so I took it to heart; I did not have the nerve to admit at the time that I didn’t really know what an Eichler was.

In certain circles, Eichler is not just a name or a style but a byword–practically a shibboleth. Eichler appreciators are almost a class unto themselves, and his homes inspire something close to a literal cult following.

And yet, some people still cannot really place the reference. “Eichler was a California guy; people in the rest of the country, even if they’re into architecture, they didn’t know him,” architectural historian Richard Brandi tells The Front Steps.

“He’s well known in the Bay Area, but unless you’re a Midcentury aficionado, this stuff gets esoteric very quickly; even many architect friends of mine don’t know him,” Brandi adds.

Many people, hearing his name and looking at his homes, assume Eichler was an architect. Actually he was a developer, working from the late 1940s through the ‘60s–and that’s why, even if you don’t know the name, you’re (possibly literally) living in his legacy.

Christian Dikas, historian at the conservation agency Page & Turnbull, tells The Front Steps that Eichler created probably around 11,000 homes in the state, including 2,500 just in Palo Alto, the greatest density of Eichler homes in the world.

(The exact number of Eichlers around is a matter of constant dispute; some sources credit him with many thousands more units.)

The famed Eichler style–”post-and-beam construction, striking roof forms, broad eaves, internal courtyards, and full-height windows that integrate the homes’ interior and exterior spaces,” as Dikas describes it, spawned so many fads and imitators that it’s almost impossible to grow up in a Northern California suburb without at some point entering a home that’s at least supposed to look like an Eichler.

A 2015 NPR story hailed Eichler as the man who “built the suburbs.” The secret of his success: “well-designed, well-built tract homes to the masses.”

They were good homes, but the secret to Eichler’s success was more than that: They were exactly the homes Bay Area needed, built exactly when the region needed them. Modern housing hawks rarely get to create new developments on that scale these days–because the world Eichler lived in was in many ways very different from our own.

Above-Average Joe

According to the 2002 book Eichler: Modernism Rebuilds the American Dream, Eichler was born in New York in 1900 to Jewish immigrant parents. He studied business and moved to the Bay Area in 1925, then worked 20 years as the CFO of his in-law’s wholesale foods company.

That sounds like exactly the kind of bucolic (if uninteresting) American middle class life that would put Joe on a straight and easy path to retirement and historical anonymity.

But Eichler rented a Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house in Hillsborough in 1943, and apparently his outlook was never the same: He was enchanted (possibly obsessed) with Wright’s use of space, calling it a “revelation.”

At the time, most critics and builders assumed modernist architecture didn’t have mass commercial appeal; that sort of thing was only meant for artists, dreamers, and eggheads.

But hey, Eichler was a middle-class guy; successful, certainly, but not a tycoon. If he loved Wright, why wouldn’t other Bay Area buyers–if only someone built homes in that style for them? He went into the building business for himself in 1947.

Eichler employed progressive, forward-thinking architects to dream up his homes. And during a period when we most associate the suburbs with redlining and other racist housing policies, Eichler defied the system and sold to every buyer, regardless of race or nationality.

At the time, Eichler tracts were a hit–and with a great many buyers, they still are. Which is where the irony creeps into his legacy.

Historically Contemporary

To be sure, part of the appeal of Eichler homes today is the allure of 20th century romance–back when the American dream was still well within the grasp of most Californians.

“Yes, I have written cute articles about Eichler owners who wear vintage fashion, fill their homes and 50s retro collectables, and the like, and even drive cars built the same year as their homes,” Dave Weinstein, editor of CA-Modern and the Eichler Network, tells The Front Steps.

Indeed, Weinstein says one of the reasons for founding Eichler Network was to lobby for the historic significance of Eichler homes as resources to be preserved for future generations.

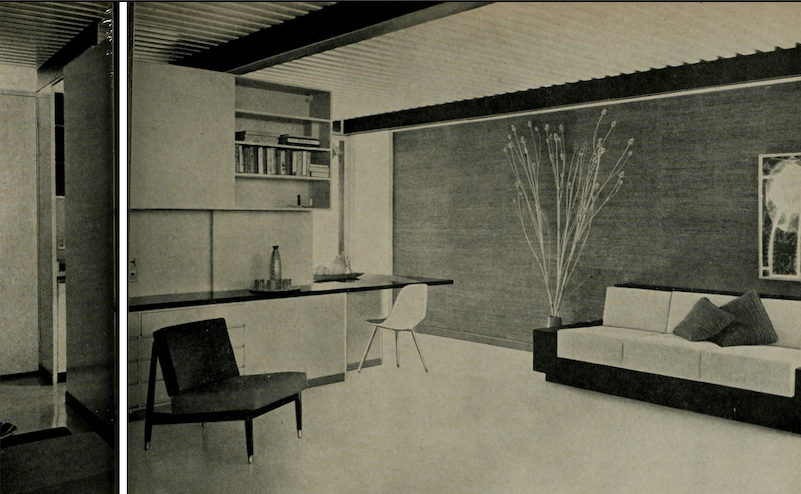

(Left: An Eichler homes ad. Right: The supposedly idyllic suburban Bay Area lifestyle was at least as much the product on offer as the homes. Photos courtesy of the 2002 book Eichler.)

In the past, Eichlers were so numerous throughout the Bay Area–and still relatively recent construction in many cases–that preservation was at best a hypothetical consideration. But now the time is swift approaching when counties that want to preserve the modernity of the past will have to take action.

“San Jose and Santa Clara County have five Eichler developments, built between 1951 and 1964,” one of them now a special conservation district in San Jose, historian April Halberstadt told The Front Steps, calling them “special homes.”

(Santa Clara County put us in touch with Halberstadt when we asked about Eichler preservation efforts; every other Bay Area county and city said either that they do not have any active protections in place for Eichler homes or did not reply to requests for comment.)

But Weinstein adds that in his opinion “nostalgia plays a relatively small role” in keeping the Eichler business in business, arguing that the quality of the homes has simply remained consistently appealing over the decades.

Eichler’s career came to somewhat disappointing end: After building the suburbs, he tried his hand at large, multi-family developments in San Francisco, like Cleary Court in Cathedral Hill and the rarely commented on Garrison Avenue development in Visitacion Valley.

Always the Utopian, he imagined revitalizing neighborhood living in SF; but many of the buyers Eichler wanted to attract to these homes had already left San Francisco to buy in surrounding areas. And unlike tract homes, it was harder to scale the budgets for these big city developments.

“He overextended himself,” Brandi says simply, eventually leading Eichler’s company into bankruptcy in 1967. He kept his hand in the housing game with smaller projects until his death in 1975, but he was never the king again, in a way undone by the suburbs he put on the map.

(Steel-framed Eichler homes under construction.)

Stuck In the Middle

Certainly his legacy has continued on without him: As the price of a home in cities like Palo Alto soars, Eichlers and even Eichler imitators now command princely sums despite their working-class roots.

Weinstein argues that it’s not an Eichler-specific phenomena; “Yes, Eichlers have appreciated wildly in price, but so have [other] little bungalows of 1,000 square feet in the same markets,” he says.

Still, the point stands: Eichler built homes for the everyday family, but those homes are now quite beyond the reach of today’s everydays.

“It’s the way the world is,” Monique Lombardelli, producer of the 2013 Eichler documentary People In Glass Houses, tells The Front Steps. “A lot of these homes were built for thousands and sell for $2.5 million, $3 million–’Mad Men’ came out and everyone was suddenly very interested in Midcentury Modern design,” she adds.

Eichler homes outcompete modern construction on the housing market because they remain human-centric and accessible, Lombardelli says: “There’s so much space and light, it’s exhilarating.”

(A modern Eichler in Palo Alto. Photo by Sanfranman59.)

Now of course, here at The Front Steps we sell many of these homes, and those multi-million dollar paydays are great news for sellers; for most people, the opportunity to put a classic Bay Area home on the market for seven figures is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and possibly a life-changing transaction.

The problem is, the Bay Area just doesn’t build like Eichler used to; since 2000, the California Department of Finance estimates that Palo Alto (for example) has added just over 2,800 new homes to its housing inventory–barely more than Eichler alone built there in a 20-year period generations ago.

Meanwhile, the population just keeps rising–from 58,000 in Palo Alto in 2000 to more than 68,500 in 2020–a pattern repeated across almost the entire region. San Francisco politicians are quick to argue that the city has built more in the past ten years than practically any point in SF history, and this is actually true–but demand continues to gobble up housing production like peanuts.

Population growth outpaces housing growth in the region large part because the idea of a single mid-sized developer creating 11,000 homes on the peninsula is frankly surreal in this day and age. And that’s the tragedy of Eichlers: Because no one else came in to build attainable, affordable homes up and down the peninsula for decades, future generations did not have their own Eichler–or Eichlers.

We only have the old Eichlers–now prized classics instead of practical commodities. And if things keep on as they are, the Eichlers of the past will have to keep serving as the Eichlers of the future as well.

As always, if you have any questions you can contact us directly, or throw them in the comments below. Make sure to subscribe to this blog, or follow us on social media @theFrontSteps too. And please do consider giving us a chance to earn your business and trust when it’s time to buy or sell Bay Area property. People like working with us, and we think you will too.

Eichler preservation is long-overdue. The responsibility lies squarely on the various cities to treasure their mid-century modern heritage as the true legacy of growth during post-war development. Why this movement has NOT been embraced boggles the mind. Take the example of the founder of Mervyn’s Department store tearing down a custom designed & built Eichler home at 71 Linda Vista in Atherton with full knowledge of it’s value only to erect a sham fake French Provincial behemoth in it’s place brings uncontrollable weeping to my California soul!